Linux, or GNU/Linux to acknowledge the large number of packages from the GNU OS that are commonly used alongside the Linux kernel, is a hugely popular open-source UNIX-like operating system.

The Linux OS kernel was first released in 1991 by Linus Torvalds, who still oversees kernel development as part of a large development community. Linux runs most of the cloud, most of the web, and pretty much every noteworthy supercomputer. If you use Android or one of its derivatives, your phone runs an OS with a modified Linux kernel, and Linux is embedded in everything from set-top boxes to autonomous cars. About 1.3 million people even use it to play games on Steam.

The world of Linux is a little more complicated than that of Windows or macOS, however. The open source nature of the Linux kernel and most of its applications allows anyone to freely modify them, which has resulted in a proliferation of different versions geared towards specific functions. Each of these distributions (or ‘distros’) uses the core Linux kernel and usually some GNU packages, and then a selection of software packages variously developed internally, taken from an upstream distro, or built from other open-source software.

Protect your privacy by Mullvad VPN. Mullvad VPN is one of the famous brands in the security and privacy world. With Mullvad VPN you will not even be asked for your email address. No log policy, no data from you will be saved. Get your license key now from the official distributor of Mullvad with discount: SerialCart® (Limited Offer).

➤ Get Mullvad VPN with 12% Discount

Thus, Pop!_OS, for example, shares most of its software with Ubuntu, from which it descends. Ubuntu was originally a fork of Debian, and still contains a large percentage of the same codebase, regularly synced. All three also use the Linux kernel and numerous GNU software packages. You can roll your own distro if you like, customised to include whatever software your use case, philosophy or personal preference demands.

This can lead to complaints about fragmentation from both users and developers targeting the platform. However, many of these distributions are closely related and the underlying Linux operating system means that – much like its Unix-compatible POSIX-compliant relatives such as OpenBSD and macOS – once you understand the fundamentals of using GNU/Linux, you can apply that knowledge to any other Linux OS and be confident that everything will work more or less as you expect.

One last point to note is that while all Linux distros rely to some extent on voluntary contributions from a community of developers for their continued development and stability, some distros are backed by large commercial software development organisations, with Canonical (which develops Ubuntu) and Red Hat being key examples. Because they benefit from full-time corporate support and upkeep, these distros are often updated more frequently than at least some of their community rivals, and may be better options for businesses who prioritise stability.

Best desktop distros

Although desktop Linux is a comparatively niche use case compared to the operating system’s ubiquitous server presence, it’s also the most fun and rewarding. An Ubuntu-based distro is currently your best bet if you want things to just work with a minimum of faff, but our favourites also include distros like Arch and Slackware, which actively encourage you to cultivate a deeper understanding of the OS underlying your desktop.

Pop!_OS

System 76’s Pop!_OS is one of the most comfortable choices for desktop Linux users who just want to get on with things. It’s based on Ubuntu, but strips out some of the more controversial elements, such Ubuntu’s default Snap package system, while adding useful features such as out-of-the-box support for Vulkan graphics. Its target audience is developers, digital artists, and STEM professionals.

Pop!_OS has a particularly pleasant graphical installation interface, designed to be quick and approachable. Its slick Cosmic desktop is based on GNOME 2, and vaguely reminiscent of macOS’s GUI layout. Future iterations are set to ship with an entirely new window manager, developed in-house by System76. System76 is also an OEM, and makes laptop, desktop and server systems, all of which run the distro by default.

Arch Linux

Arch is a thoroughly modern, rolling-release distro that nonetheless aims to provide a classic Linux experience, giving you as much hands-on control over your OS and its configuration as possible. You’ll have to choose your own desktop environment after installation, for example.

Its official repositories typically update quickly enough, but these exist alongside the bleeding-edge community-driven AUR (Arch User Repository) system, from which you can compile packages and install them as usual via the pacman package manager. For those who don’t want to drive straight to the DIY ethos, Manjaro is the most popular of its derivatives, built to be more beginner-friendly, with a graphical installation interface and quality-of-life tools for driver management.

Ubuntu

Based on Debian, Canonical’s Ubuntu Linux shares a significant chunk of its architecture and software, such as the friendly apt package management system. But it brings a lot of unique features to the table. Canonical’s Snap packages, for example, are designed to make it easy to package and distribute tamper-proof software with all necessary dependencies included, making it extremely well-suited to office workstations.

Ubuntu operates on a fast development cycle, particularly compared to Debian’s slow but stable releases. It also cheerfully provides proprietary drivers and firmware where needed, and, although Ubuntu itself is fully free, Canonical is here to make a profit, meaning that enterprise-grade support contracts are available, and the developers’ approach to security is tuned to the needs of business.

Debian

One of the longest-established distros, dating from 1993, Debian has numerous popular derivatives, from Ubuntu to Raspberry Pi OS. It introduced the widely-used and much-cloned apt package management system for easy software installation and removal, and to this day prioritises free, open and non-proprietary drivers and software, as well as wide-ranging hardware support.

While Ubuntu and Red Hat are tailored to enterprise, Debian remains a firmly non-profit project dedicated to the principles of the free software movement, making it a good choice for GNU/Linux purists who want a stable OS that’s nonetheless comfortable to use, with a variety of popular GUIs to choose from.

Slackware

Another 1993-vintage distro, Slackware (no relation to the popular collaboration platform) is still very much alive and kicking, despite a website whose front page was last updated in 2016. That’s set to change soon with the imminent release of Slackware 15.0, which those who want the latest features can already access in the form of Slackware-Current.

As you might gather from the slow release cycle, Slackware is built for long-term stability. It also maintains a number of classic Linux features that other distros have abandoned, making it a popular choice with many old-school users for that very reason. It uses a BSD-style file layout and hands-on ncurses installation interface, is deliberately “UNIX-like” and, most notably, eschews Red Hat’s now-ubiquitous systemd, so you’ll be using init rather than systemctl commands to manage services. Refreshingly, it boots to the command line by default, but you can choose from a range of desktop environments. You’ll probably also want to add a package manager such as swaret.

If you want a “pure” and slightly old-school Linux experience, Slackware is an excellent choice and a great way of getting a handle on the underpinnings of Linux as an OS. It’ll run on almost anything, from a 486 to a Raspberry Pi, to your latest gaming PC, with support for x86, amd64, and ARM CPUs.

Best lightweight distros

Not every PC is an eight-core gaming behemoth with 32GB RAM and the latest graphics card. But versatile, lightweight Linux distributions mean that an underpowered netbook or Windows XP-era PC can be brought back into use as a genuinely functional home computer, with all the security updates and modern software support that you’ll need.

Puppy Linux

One of the best-known lightweight Linuxes, Puppy Linux isn’t a single distribution, but rather a collection of different Linux distros, each set up to provide a consistent user experience when it comes to look, feel, and features. Official versions are currently available based on Ubuntu, Rasbian, Debian, and Slackware, with both 32- and 64-bit versions available for most of these.

They’re all designed to be easy to use for even non-technical people, small – around 400MB or less in size – and equipped with everything you’ll need to make a PC functional. Having to choose your Puppy can be a little confusing, but there’s a guide to help you through it. Although 32-bit CPUs are supported, you’ll want an Athlon processor or later for more recent versions to be viable. For more modern systems, note that Puppy doesn’t support UEFI, either, so switch your BIOS into legacy mode before installation. ARM architecture is also supported in the form of Raspberry Pi.

Ubuntu MATE

Ubuntu MATE – pronounced mah-tay like the hot beverage – isn’t the absolute lightest-weight distro around, requiring at least 1GB RAM and a 64-bit Core 2 Duo equivalent processor. It is nonetheless a superb choice if you need to bring an elderly home PC or underpowered laptop back into viable use.

The MATE desktop environment is popular with Windows XP veterans and comes with tweak tools already installed for easy customisation. And as it’s an Ubuntu variant, you get that distro’s wide-ranging repositories, excellent hardware support and easy gaming, with a user interface that’s a bit lighter and more comfortable for Linux newcomers.

Although a 32-bit x86 distribution is no longer available, you will find both 64- and 32-bit versions for Raspberry Pi, and versions specifically designed for a small range of pocket PCs.

Tiny Core Linux

A few versions of this ultra-lightweight distro are available to download: A fully functional command line OS image (16MB), a GUI version (21MB), and an installation image (163MB) that’ll support non-US keyboards and wireless networking, as well as giving you a range of window managers to choose from.

As you’d assume from its minuscule file size, Tiny Core doesn’t come with much software by default, but its repositories include the usual range of utilities, browsers and office software that you’ll need to make use of your PC. You can run it on a USB drive, CD, or stick it on a hard disk, and it’ll work on any x86 or amd64 system with at least 46 megabytes of RAM and a 486DX processor, although 128MB RAM and a P2 are recommended. Arm builds are also available, including Raspberry Pi support.

Best enterprise server distros

In practice, most distros that are good on the desktop are entirely adequate for use as part of your enterprise server infrastructure, although you’ll probably want to install a version without a graphical desktop for most use cases. If you operate an enterprise server, you’ll want something with stable Long Term Support versions, responsive security updates, and that’s familiar enough to make it easy to troubleshoot. Right now, Ubuntu and Red Hat derivatives are particularly solid choices.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux

Red Hat Enterprise Linux is synonymous with big business. Although RHEL’s source code is, of course, open, it uses significant non-free, trademarked and proprietary elements, and updates that you need a subscription to access. Red Hat emphasises security, hands-on subscriber support and regulatory-compliant technologies and certification. Its developers also put a lot of effort into its enterprise-grade GUI, which can be more comfortable for those who’d rather not do all their configuration at the command line.

Red Hat itself – now a subsidiary of IBM – has contributed important elements to Linux as a whole. With fully free community Red Hat derivative CentOS’s move to give up Long Term Support (LTS) versions in favour of a rolling release model (via CentOS Stream), RHEL is perhaps the best option for consistent, long-term stability for anyone who requires a Red Hat based Linux distribution for business use.

Fortunately for SMBs, the no-cost version of RHEL has been expanded to compensate for the loss of traditional CentOS, allowing individual developers and small teams with up to 16 production systems to get a free subscription, providing access to the distro’s update repositories.

Amazon Linux

Amazon’s own Red Hat derivative, Amazon Linux, is designed to work optimally on the cloud service provider’s platform. It supports all features of Amazon’s EC2 instances and its repositories include packages designed to seamlessly integrate with AWS’s many other services. Long Term Support versions are available, making it an appealing CentOS replacement, as long as you’re happy moving your machines to the AWS cloud.

Although its VM image and containerised versions are designed first and foremost for deployment on AWS, you can download VM images for on-premises use if you want them.

While Amazon Linux is based on CentOS, its successor, Amazon Linux 2022, is built on Fedora, but respecc’d as a server distro.

Ubuntu Server

While most desktop Linuxes are just as capable as servers, we’re going out of our way to recommend Ubuntu for both, as it’s incredibly easy to roll out a wide range of secure and fully-functional servers from its packages. It’s also free and conspicuously quick when it comes to security updates.

Its Long Term Support versions get five-year security and ten-year extended maintenance guarantees. As well as x86 architecture, it’s available for ARM, as well as IBM’s POWER server and Z mainframe platforms, although its legacy hardware support pales in comparison to Debian’s.

Ubuntu is entirely free for everyone, but you can subscribe to Canonical’s commercial support if you need it, and Ubuntu’s popularity means that it’s widely supported by third-party firms and community forums.

Best security distros

Some people use Linux because it’s free, or because it’s fun to tinker with, or because they don’t like being beholden to a large corporate entity. Others use Linux for security: either to maintain it or to test it. There are a number of distros designed for those who want to lock down their privacy and security at all costs, as well as distros built for infosec professionals who need to make use of more specialised tools.

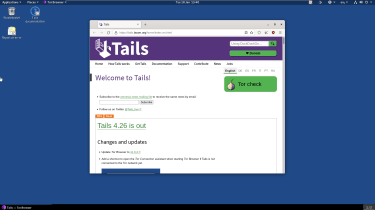

TAILS

If you work on other people’s computers or on public networks and you’d like to minimise the risk of your identity, communications and data being compromised, TAILS is the OS-on-a-stick for you.

Based on Debian, TAILS’ most distinctive feature is that it routes all internet traffic via TOR by default and, when used as a live distro, it lives on an 8GB+ USB stick and runs in RAM, leaving no trace on the host PC unless you deliberately choose to do so. The 1.2GB live image includes a GNOME 3 desktop environment, with all the conveniences of a modern desktop Linux.

Kali Linux

Built for penetration testing, vulnerability assessment and other red-team-oriented security tasks, Kali is definitely not an appropriate choice for an everyday desktop distro. That doesn’t mean it lacks quality-of-life features, though. It’s based on Debian and includes the lightweight Kali Linux Desktop environment (based on the Xfce window manager) by default, with GNOME and KDE Plasma versions also available.

Nice though the UX is, it’s the ready-to-go security tools that Kali’s users are here for. A wide range of 32- and 64-bit images for a range of platforms and use cases are available, from password cracking to VoIP research and RFID exploitation. Kali ships with up to 600 security tools, but there are vanishingly few use cases that will call for all of them. Specialist hardware support includes Kali NetHunter for Android devices and a range of ARM images, including Apple M1 architecture.

There’s a guide to help you work out which you need, and storage requirements range from 2GB to 20GB. If you opt for a minimal install, you can use metapackages to pull down exactly the toolkit you require. Paid-for customer support is also available from developer Offensive Security, which also provides courses and technical certification.

ParrotOS

ParrotOS is a single distro with two versions. Both are based on Debian’s Testing tree and are available with the MATE, KDE and XFCE desktop environments.

Home Edition (shown here) is designed to be a lightweight daily use OS with a focus on privacy and easy-to-assemble penetration testing tools if you need them.

It’s not as private as TAILS’ amnesiac live distro, but comes installed with privacy-oriented applications for secure file sharing, cryptography, end-to-end encrypted communications applications and Anonsurf to proxy all online traffic via the TOR network.

ParrotOS Security Edition, on the other hand, is a Kali Linux alternative, packed with penetration testing and digital forensics tools, from network sniffers and port scanners to password attacks, exploits, and car hacking tools.

Unlike Kali, ParrotOS is a community project. While this means there aren’t any enterprise support options, it is closer to the GNU/Linux ethos and there’s a reasonably active user community to provide support.

Some parts of this article are sourced from:

www.itpro.co.uk

New Vulnerability in CRI-O Engine Lets Attackers Escape Kubernetes Containers

New Vulnerability in CRI-O Engine Lets Attackers Escape Kubernetes Containers